Via Philly.com: Putting the brakes on kids’ screen time

Screen time is serious business. It’s more than just playing games and checking social media. Digital devices give kids access to the entire universe. Parents, let alone children, have a hard time managing the constant bombardment of information and misinformation. Supervising and limiting its use is critical.

Philadelphia-based adolescent psychologist and author, Michael Bradley, Ed.D., goes even further stating, “Parents were taken by surprise when it came to video games, computers, and smartphones. This proved to be a huge mistake.” Now that we know their astounding influence, it’s time for parents to, “take back control.”

Easier said than done!

My advice for parents is to remain confident that limiting screen time is necessary for the physical and mental wellbeing of your children. It will be worth the time, effort, battles, and constant surveillance. Your children’s futures may depend on it.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says:

“What’s most important is that parents be their child’s media mentor. That means teaching them how to use it as a tool to create, connect, and learn.”

For parents, that also means setting rules and sticking by them. Where to begin?

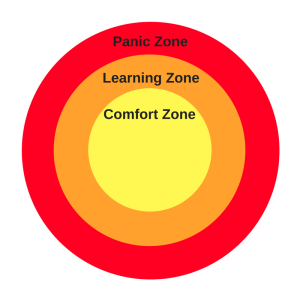

Start with a frank discussion about why you’re doing this and how critically important it is. Tell your kids that you don’t let them ride in a car without a seatbelt, drink, or take unprescribed drugs, and you won’t let them use digital devices without supervision and restrictions.

In order to do this, the AAP recommends that parents and caregivers develop a family media plan taking into account the health, education and entertainment needs of each child as well as the whole family.

“Families should proactively think about their children’s media use and talk with children about it, because too much media use can mean that children don’t have enough time during the day to play, study, talk, or sleep,” said Jenny Radesky, MD, FAAP, lead author of the policy statement, “Media and Young Minds,” which focuses on infants, toddlers and pre-school children.

The AAP recommends that parents and children work together to develop individualized Media Use Plans taking into account:

- an appropriate balance between screen time/online time and other activities,

- setting boundaries for accessing content

- guiding displays of personal information,

- encouraging age-appropriate critical thinking and digital literacy,

- supporting open family communication,

- implementing consistent rules about media use.

To help get started, you can access the AAP’s interactive online template which is easy to complete and provides lots of opportunities for personalization.

There are also many other online contract options available which are age specific and run the gamut from short and sweet to highly specific such as:

A Family Media Contract from Common Sense Media

A Family Contract for Online Safety from Safekids.com

And no matter how complete a contract may be, you should also consider using parental controls. Common Sense Media offers the following advice:

“Even if you’ve talked to your kids about screen-time limits and responsible online behavior, it’s still really tough to manage what they do when you’re not there (and even when you are).

Parental controls can support you in your efforts to keep your kids’ Internet experiences safe, fun, and productive. But they work best when used openly and honestly in partnership with your kids — not as a stealth spying method.”

The bottom line is that a contract or a software package can’t keep your kids safe when using digital devices. The best chance for that is keeping the lines of communications open between you and your kids. Letting them know how much you love them and that keeping them safe and healthy is your number one priority.

No one said this would be easy, but it’s certainly worth the effort. So take a deep breath and get started.